Brain Chemistry, or why people with ADHD can't just "turn it off" (Part 1)

ADHD is very misunderstood as a condition. It is not just a mental health condition, but is an inability for the human brain to produce and regulate dopamine effectively. This causes issues because in those with ADHD, a lack of dopamine means the brain can't manage behaviour appropriately.

It's ADHD Awareness Month this October, and as such I'd like to share a little bit of what ADHD is along with my own experiences. I'll start off with a "simple" question: what is ADHD. The technical definition is "Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder is is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders of childhood. It is usually first diagnosed in childhood and often lasts into adulthood. Children with ADHD may have trouble paying attention, controlling impulsive behaviours (may act without thinking about what the result will be), or be overly active." However, for most people, their experience of someone who has ADHD is behaviour similar to that reported in my Year 11 report card.

"[Adam] is not achieving to his ability level, mainly due to concentration problems... He needs to accept that in lessons his work and the rights of others to learn must take priority over socialising... He needs to aspire to more than just 'C' range ratings."

I was the penultimate "pain in the butt" kid in class, the archetype that my wife remembers as "that annoying boy in class who just wouldn't let us enjoy movie day in English class without disrupting the room in some way." Unfortunately, because a lot of people grew up with "that kid" in their class, they tend to view people who have ADHD or ADHD-like behaviours quite negatively, because quite frankly at the time we were annoying. Even though I had 12 report cards with similar comments from over 20 different teachers, no one ever had me sent to a medical professional to look into behavioural problems during my whole time at school. It was written off as "oh just something Adam does", even though there were clear periods where I would achieve A+ in a subject, to only descend back into C in the next semester. I wasn't diagnosed until I was 29 years old.

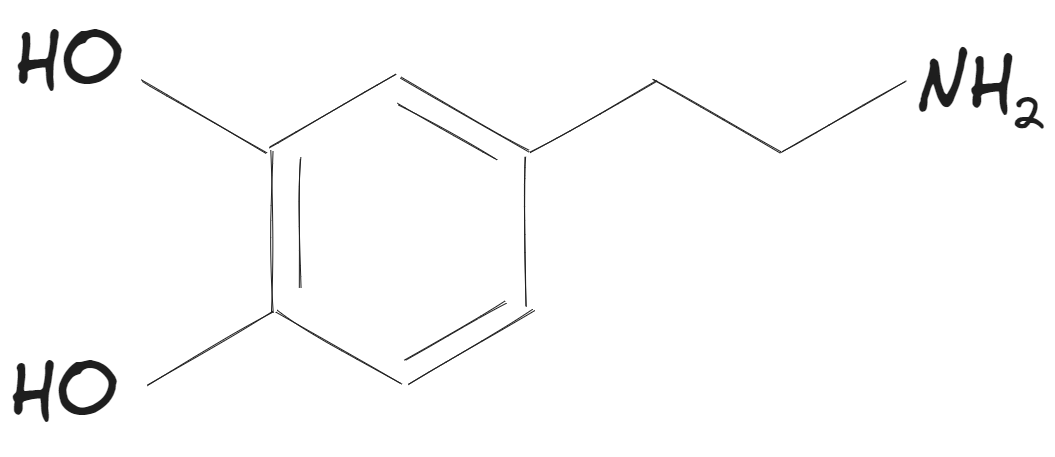

The reason for my performance swings came down to one chemical: Dopamine (pictured). Dopamine, known as the "reward" chemical is responsible for giving you "feel good" vibes. The brain uses Dopamine to regulate emotion and behaviour via the addition or removal of it in your body. If you do a good thing, you get a bit of Dopamine, and, if you do a bad thing, the brain takes it away. In neurotypical people, this is achieved by the brain having an "average" amount around so adding/subtracting makes a difference in your mood. This average amount in your brain also gives you motivation to start (and complete) tasks that you do not want to do. It's a simple system that works to great effect.

In those with ADHD, their brains have very low amounts of naturally occurring Dopamine. This has the following effects:

- Low motivation: due to a lack of Dopamine in their brains, those with ADHD have trouble getting anything started because there is no initial "nudge" from Dopamine.

- Poor impulse control: as there is no Dopamine to take away, when a person with ADHD does something negative that their brain doesn't want them to do, it can't effectively "punish" them. This means there is no natural backstop to prevent poor behaviour.

- Hyper focus: when the body finally lets go of a bit of Dopamine it can completely change the behaviour of the person. This could be anything from "wow little Johnny has been drawing for the last 6 hours, he must really enjoy it" to quite destructive addictive behaviours.

The reason why stimulants are a common prescription for those with ADHD is it allows the body to maintain an "average" (albeit artificially created) amount of Dopamine. The body can then regulate behaviour, emotion, and executive function more effectively. However, this is not a silver bullet, so don't assume just because someone is being treated for ADHD that is all they need. Additional sources of treatment can include working with a psychologist or counsellor on practical ways to improve.

In Part 2, I will go through what the brain looks like for those with ADHD in comparison with a neurotypical brain. In part 3, I will talk a little bit about hyper focus and how even something that seems "good" can have quite severe side effects in our personal and professional lives.