Thirsty Brains, or how Dopamine is(n't) regulated in those with ADHD (Part 2)

In our last article, we spoke a bit about Dopamine and what it does for the human brain. Today, we're going to discuss a little bit about the specifics of how Dopamine works (or doesn't) in the brains of those with ADHD.

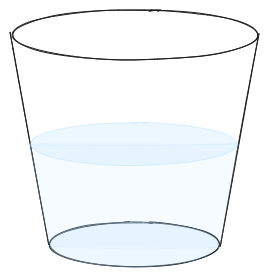

To make this easier, consider a cup that represents Dopamine levels in the human brain. In neurotypical individuals this cup is half full and represents a steady state where the brain has can easily influence executive function by reducing or increasing levels in the brain. Adding Dopamine results in a "reward" and encourages the person to continue engaging in their behaviour, and removing Dopamine results in a "punishment" where the person is discouraged from their behaviour. At a high level, this represents how executive function works in the human brain.

However, in those with ADHD the brain fails to maintain a half full cup, and usually keeps it quite empty. Then, during a reward cycle the "increased" Dopamine is usually much less than would be seen in a neurotypical brain. This means that in general, those with ADHD lack motivation to start tasks, and even if they do get started the rewards are so paltry that they give up much quicker than neurotypical individuals. On the flip side of the coin, when someone with ADHD engages in a negative behaviour, their brain has no way to punish them. That's why they are generally poorly behaved: when they do something bad, people tell them it's bad but their brains are just like "meh".

From my own personal experience, I had one thing that I just couldn't kick when I was a kid (and honestly well into my 20s): if you wanted to keep a secret you shouldn't have told me. It'd be out on the streets in three seconds. In 99% of cases, these secrets were quite banal so no one ever got too upset with me if I spilled their confidential dealings. When people told me I should stop doing it, it was just water off a ducks back: you might as well have been telling me not to breath, "what was the big deal?". Well, when I was about twenty two - give or take a year - a colleague shared something with me and I truly didn't understand it was a secret. I'd never developed a real appreciation for "subtle" secrets or an idea of what someone making me their confidant really looked like. Most of the time I was playing World of Warcraft, and who cared if Joe the Rogue ninja looted from his 30th Deathwing kill? Well, this colleague had shared with me that they were looking for another job. In my mind I didn't think it was a particular secret - they were unhappy in their job, and were vocal about it. I knew not to tell their manager, but I thought their colleagues knew (or at least had a really good idea). When I was in a meeting discussing problems with the team, I revealed what this person had confided with me, and they exclaimed "Adam! What are you doing!? I told you that in confidence!" I was stunned.

I had grown to see this person as a mentor, and their exclamation and look of shock made my blood run cold. Their visceral reaction to me revealing their secret had for the first time in my life made me feel deeply horrified that I'd shared a secret beyond myself and the person confiding in me. From that moment forward, my behaviour changed because I had been shocked to my core; I developed a keener sense of empathy so that I could understand context more deeply during conversations. I was lucky enough to have this epiphany when I was young, because if it hadn't happened then I could still be happily spilling secrets all over the countryside and be none the wiser. But this is the problem with ADHD: executive function doesn't, well.. function all that well. As a consequence, it takes very extreme circumstances to reinforce a behaviour. So while I have been able to adapt and grow, that came at a great cost to a personal relationship I had with someone I admired. You will find this same theme among most people with ADHD: irregular personal growth spurred by very dramatic and sudden crisis that are bought on simply because we don't have the capability to truly understand the impact of our actions until it is too late.

This of course, doesn't excuse the conduct. But, you will be hard pressed to find someone with ADHD who, when faced with with a scenario where themselves or others have been hurt or let down by their actions have failed to actually grow from that experience. People with ADHD can be kind, loving, thoughtful, and empathetic but sometimes we just need a little more patience and guidance than most people (or a sharp reality check). If you're finding yourself annoyed or frustrated by someone with ADHD, consider a conversation before an argument. Especially when dealing with Children with ADHD, remember that a positive interaction with a sympathetic adult now could make a lifetime of difference.

For my last article, I'll be talking about how hyper focus or what happens when the cup from earlier decides to actually fill up.